The future of branding (and to a lesser extent, basketball) rests in the hands of the world's best basketball player and his 26-year-old best friend. Now all they have to do is put down the videogame controllers.

Rising from his throne like an urban fairy tale, the great black king stands in his glass house. Looming erect, at six feet eight inches and 250 pounds, he is a pythonic force of length and clout, and all he has to do is crane his neck just so to ever so politely, gingerly, and revolutionarily break the glass ceiling.

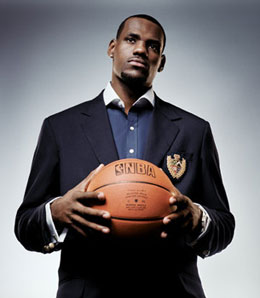

The king is wearing sneakers, not the roughed-up kind but the endorsement kind. You can see them, big and exclamatory, through the cameras in the Cube, where he's having his video portrait taken. Twenty-four lenses shooting in adulation from every angle. It's a tiny space, and he fills it. His sneakers take up space, too. They're the dark-red Air Force Ones. Shiny like status. When he misses a shot, he stamps one, a monster foot. The bright-white laces fly, the swoosh goes slap.

He roars. Really, he fucking roars when he misses. Outside the Cube, uptight people titter nervously; they drop their mouths and look up from their bottles of unfortified water.

Was that even human? they ask one another's unfamous faces.

He's a king because they are not. You take away the basketball, and that's still the point. A king can only exist if there are subjects to kneel before him.

He is encased in glass, a great fly caught in commercial amber. Inside he's doing exactly what he wants, playing NBA 2K8 on Xbox 360 -- the hottest console! -- with a neat pile of Vitamin Water -- that quenching endorsement! -- in the corner. Jay-Z is thumping from the speakers like a promise. Outside are the reporters, the gawkers, the handlers, the stylists, watching the way unimportant people do. Waiting, charting, and hovering, like insipid gray suits selling Red Bull at a rave, and club-loud LeBron James is on the inside playing a video game.

This is the story of America Tomorrow. The future of this country. The supersized, jumbo-jawed metaphor for the watchers and the watched is right here in a glass cube, endorsing himself, becoming the future so adroitly that nobody cares that the rest of us are still standing dumbstruck in the present.

To watch LeBron James play is to know that you are not a superstar.

Watching him coming down the court, not terribly fast but not slow for his size either, he is this game's animal, a beast made of pistons, a dark gazelle. Built in a rubber-smelling, pimple-walled orange lab by men with basketball faces. Evolved from a different species.

Picture it. Michael Jordan (his hero) and Penny Hardaway (his full-court predecessor) made love and sprouted this beatific embryo, then gave it to Kobe, who tucked it in his Armani pocket, nestled and incubated it, and when it hatched, the progeny was longer and stronger, and it had more tattoos than its parents, a bigger smile. Love me, market me. You will do both. Love and marketing will, through me, become inextricable.

But the truth is more like this: At twenty-three, LeBron James is only a living thing with a ball in his hands. There is an affection between the two. Love you can't grasp. It's not a middle-class marriage; it's Romeo and Juliet high on Spanish fly and Carmelo Anthony buckling like a horny cheerleader before it. Other players fold to it, like, "Here, you better take it, here, here, hereherehere," and they pass it off to him -- a hot potato that cools to his touch, that wants him to handle her.

LeBron plays without a discernible disposition. When a teammate goes to help him up when he's down, it's a dead man's stare. An ESPN blogger dubbed it the LeBron James "Don't Help Me Up, I Don't Even Want to Look at You Because You Suck So Much, I Can't Believe We're on the Same Team" face.

But he's not an asshole. It's rawer, purer, and a lot less believable than that. He says, "It's just having this instinct. I see the plays over and over in my head. Even when I'm dreaming, I dream about basketball. So when I'm playing, I see the play before it ever even happens. I dream about it, and then I make it a reality."

His voice is hormone deep. Gone-through-five-changes deep. It is bearded but young.

Game Five, Round Two of the Eastern Conference Finals. Cavaliers at Boston. It smells like basketball, the sweat and the shine of the floor. At one point, Boston fans start to rally hard, and LeBron scowls at the crowd, like, Yeah, go on and rally, motherfuckers. There are five of them. There is only one of me.

Boston takes it, 96 -- 89. LeBron scores 35 of those 89.

At the press conference afterward, diamonds glinting -- earrings, ring, cuff links. A six-foot-eight badass blinged up. He is asked how bad the Cavs need to win now. He says: "LeBron James's team is never desperate." Numbly, directly. Look at my diamonds.

On his leg there's a tattoo that says WITNESS. At a game once, slight, myopic billionaire Warren Buffett sat and watched and wore a T-shirt that said the same. They met a few years ago, ate cheeseburgers together. Buffett's a big fan; he believes LeBron will sit at the billionaire's table, with his lobster bib and his golden chalice.

But witness?

"That," says LeBron, "is for everyone that watches me play. They witness something special. You're all a witness."

In his glass house, he is this brilliant museum specimen. Observe him, this great black fly mouthing the words to a rap song and toggling a controller with the zombie gaze of a child. Look at him, but don't touch. Look, you are here to look, but do not disturb.

One guy tries. "LeBron? Um . . . " The name LeBron on his tongue is an apology. "Um, can you . . . "

LeBron says one more minute. He's been playing for forty. He wants to finish his game.

"You need him out? I'll get him out." This comes from a dude a little older than LeBron, dressed a little more like a man.

He knocks on the door of the Cube. "Yo, 'Bron, let's go. Time to go."

Just like that, LeBron is out.

This is Maverick Carter. He's LeBron's best friend; they grew up together in the Akron projects. He's also LeBron's other half, older brother -- the business partner who counts the money.

Sometimes he is Momma Bear. They are eating salads. LeBron finds a piece of bacon in his salad and is inspecting it, wondering if it's bacon. It's okay if it is bacon, he likes bacon, but he's not sure if it is. Maverick sticks his palm out, "Let me see it." Turns it over with his fingers. It's ascertained that it is, indeed, bacon, and he tells LeBron so, and now LeBron wants it back. Maverick shakes his head, smiles. He is shrewd, caring. He is both at once. Business and not-business, the fusion of the two. How this empire is evolving, as organically as talent and yet also as plastic as Taiwan.

There's a child hovering near the Cube. Maverick asks, "Who's your favorite ballplayer?"

Kid says, "Um . . . do they have to be players who are playing now?"

"Not at all."

"Um . . . Michael Jordan. Julius Erving. Um . . . "

The kid's dad teases, "You better say LeBron!"

Maverick says, "Nah, that's cool," and he's smiling, he's genuine with children, or at least wolfishly good at pretending, but you can see his brain working: How can we make sure this kid, and billions like him -- black ones, white ones, Chinese ones -- say LeBron James first? And LeBron James only.

In 2005 LeBron fired his superagent, Aaron Goodwin. Aaron Goodwin who represents Kevin Durant and Delonte West. Aaron Goodwin who began courting LeBron when he was a moist high schooler back in 2003. Aaron Goodwin who got him the famous $90 million deal with Nike.

In his place, LeBron hired Maverick and started his own agent and sports-marketing company LRMR: The L stands for LeBron, R for Richard Paul, M for Maverick Carter, and R for Randy Mims -- all of them childhood friends. This is well publicized, the usual shit said about it: Entourage but black -- and basketball. Dumb move. Wait, does it even matter when LeBron James is the product? Nike would do business with a roundtable of squirrels to get LeBron to lace up their shoes.

Except Maverick isn't a squirrel. He is twenty-six and well connected. He's got a sleepy voice and a charming sharpness to his face, plus the "I am your friend, I am not your friend" back-and-forth business in his eyes that the hottest bitch in high school harnessed like a Bubblicious smack.

He is the CEO of LRMR. Also, he is the gatekeeper. You want LeBron, you don't just go to Maverick. You have to go through Maverick. He didn't finish his sports-management degree at Western Michigan University. Instead, Maverick went to the Harvard of sports management, Nike, and apprenticed for a year and a half under Basketball Senior Director Lynn Merritt, who was the first convert to the Religion of LeBron. Merritt called Maverick a sponge. He listened to everything. He asked questions -- he asked, Who is the best at this? At that? -- and then he drew from them the answers.

But imagine the beginning, imagine the NBA hearing its newest, biggest star fired his agent and put his best friends in charge. A couple of kids in a designer tree house, watching as they burn down their parents' estate. Now imagine the smoke clearing, when LeBron and Maverick began inking more and more deals, and it became clear to Goodwin that not only did the king have a new kingmaker, but that suckling kingmaker was actually building the empire he'd always dreamed of.

At a lunch following his charity bike-a-thon in Akron, there is all manner of fried chicken being passed around. Boneless, barbecue, buffalo. Orange, red, and steaming. LeBron sits in the way corner in the way back of a pub with his inner circle, Maverick and Mims, and LeBron's Olympic teammate Dwyane Wade. Lunch is laughing, loud. They talk about their BlackBerrys, how to get the calendar to display like this or like that. Kid businessmen with Monopoly cash.

"I thought," says LeBron, fingering a pineapple slice, "if I stopped playing basketball right now, what would my friends have to look back on? They wouldn't have anything to look back on. For me to grow as a businessman, and for me to become a man, I decided I've got to start working with guys I can trust -- my friends. Now I don't need to be there for them to get into places, high-prestige places, or to have a business meeting with somebody. LeBron doesn't have to be there."

He's the guy who started seeing the hot chick, in part to land his friends dates with her rosy clique. Everybody gets laid.

Under the table, LeBron's big-sneakered foot is underneath Maverick's. Their legs are touching, their expensive sneakers are canoodling. It is the ease of their friendship, of their closeness, that they don't even notice.

You can see they've talked this over. LeBron and Maverick. They've sat around on gaming chairs, around an Xbox campfire, and they've said, "I've got it, I've got it, we don't do sponsorships, we do partnerships." And maybe Maverick sponged it half off of someone in a Nike boardroom and half off of Jay-Z, but it doesn't matter. Because the reason this business model will work is, here are the most popular kids in school, and now in life, and they are the ones commandeering the bake sale. Nobody wants to be in a partnership with a loser. You want someone who is airborne, someone who can control climate, the guy who can get the girl and win the game and who looks good with his shirt off.

"What are we doing differently?" says Maverick, and you can tell he loves this question, and loves his answer more: "One thing we do differently, we like to control -- well, control is a bad word -- we like to be involved in every aspect of the brand we're partnered with: who they're advertising with, what the advertiser looks like -- if it's a commercial, then who's the director? We really strive on the management side once a deal is done, so it becomes a partnership, not just a deal where they pay LeBron, he shows up."

And about the partners, they all need to be authentic. Capitalize it. AUTHENTIC. It is a word Maverick and LeBron found in a glen one day, a tethered unicorn they unfettered and dusted off and made their into-the-sunset horse.

So let's say some local car dealer, not even from Akron but from, say, Tallahassee, offered you guys $40 million a year, would you say no?

Maverick says, "Absolutely. If it's not AUTHENTIC to LeBron, then definitely not. We don't do sponsorships. See, sponsorship is" -- he points to the State Farm logo on one of the bike-a-thon banners -- "State Farm pays, then they get to put their names on it. Partnership is: State Farm pays to put their name on it, but they also bring something to the table. Instead of just money."

It's charming to be in control.

"The biggest deal we've said no to," Maverick says, scratching his chin and considering the options, "was $2.5 million a year. Now that's per year. Four years. Per year. It wasn't necessarily that the brand wasn't right. It just wasn't the right time for LeBron to do it."

It's charming to say fuck you to $10 million.

"It's mostly my responsibility," Maverick continues. "LeBron focuses on being the best basketball player in the world. I do most of the negotiations. He's gonna help, but it's not like he's involved in negotiation. That's why it's important to establish the team. He does come in on top-line meetings. But he's not going back and forth on e-mails. He's involved from a top-line perspective."

LRMR owned about 10 percent of big bicycle manufacturer Cannondale with private-equity firm Pegasus. Sold it a few months ago. "LeBron and I came up with the idea," Maverick says. "We discussed it with a member of our team who handles the investments, and we said we were interested in the business of bikes. Twelve months later we sold it with Pegasus and made three or four times as much."

There is the Play-Doh sniff of little boys playing at grown-up games -- Chutes and Ladders with solid-gold game pieces. They have the best of everything. LeBron chose Maverick, and Maverick in turn chose a Valhalla.

But there is also something else: LRMR isn't just looking for equity from the business of LeBron; they are looking for equity from other ballers. They are expanding into a full-blown marketing agency. So far, they've signed Mike Flynt, Ted Ginn Jr., and most notably, new Memphis Grizzly O. J. Mayo. The latter chose to enter the NBA draft over finishing college and was considered one of the best high school players in the country. Sounds familiar.

An athlete representing another athlete. This is a revolution in itself, according to Kenneth Shropshire, a professor of sports business at the University of Pennsylvania. He's never heard of anything like it. And he imagines that's the way it will go. Not just athletes representing themselves, but things happening sooner, faster, fiercer.

"The next step would be for an athlete to come out of high school with their own company," says Shropshire. "You see LeBron, and an even younger kid thinks, Hey, this is something we can do!"

The LeBron Effect is that you can no longer come into the game at twenty-five and expect to get better endorsements than the guy who came in at sixteen, who has employed an agent since he was twelve. You will have lost the race before you even got your number. It's like the younger sisters of prom queens wearing progressively shorter skirts. Show it sooner and let them taste it closer, and suddenly it's, Screw your older sister. She's class of 2008. Not just old hat, but fucking porkpie.

The partners have found their horse. Here in this room, they are betting wild trifectas with seersucker money. With his wide lap, LeBron James straddles all the odds:

He is self-aware and self-ecstatic, in the quietest of ways. "I grew up in Akron, and there was no LeBron James to look up to," says LeBron James.

He's kind of funny, for an athlete. "You grow up in Chicago, you got Walter Payton, Michael Jordan. You grow up in Akron, you got Goodyear!"

He thinks beyond himself, even in the third person. "Me and Mav were talking the other day: We were saying, on June 17, during the NBA Finals, we hope the Lakers win, because Kobe sells shoes, and that helps basketball. That helps LeBron. That helps LRMR."

He is unpretentious. "I was on the cover of Sports Illustrated when I was in the eleventh grade, and I just thought I was doing another cover of another sports magazine. I didn't know how big it was at the time. I didn't know till I was like twenty-one years old how big Sports Illustrated was, and then I was like, Wow! I was pretty big in high school!"

He self-actualizes. "Then I've got a lion tattoo, which symbolizes me. I mean, I've always loved lions. I don't know. I love lions. They the best."

BUT.

There's this: Ask him what his favorite drink is, what he likes to order when he's out, and you mean cocktail, but right off, LeBron says Vitamin Water. Fast, like this: Vitamiwater, like he's spitting out a Jeopardy! question before anyone else in the room. It's rumored he peels the labels off bottles of water he's drinking if they're not Vitamin Water. He's a raging endorser; thanks to Maverick, he is always on. He knows how to be bipartisan, modeled after Jordan.

But he doesn't have the Jordan glimmer yet. LeBron hasn't proven it yet. Because he's not Jordan. Yet.

You hear this from the fans, the guys who love this game enough to recite its truths like drama majors geeking out on Shakespeare.

Go to the famous West Fourth Street court -- the Cage -- in New York City and ask around. These men, their kids, they love LeBron, they wear his sneakers. But Jordan is still better. Jordan's toilet flushes with legacy. He is a proven commodity, as worshipped as the sun, the same bright need in every country.

On a hot summer Sunday down at the Cage, an eleven-year-old named Clifton is watching a game with his uncle. Clifton says, "I love LeBron, but I'd rather meet Jordan." Why? "Jordan's more famous." His uncle Wayne pipes up: "This kid probably never even seen Jordan play. I'm forty-seven, I've seen everybody play since I was his age, and I've never seen anybody play like Jordan. Man, MJ took it to another level."

Then you've got this baller, Victor "Gotti" Cherry, thirty-three, with a sly tuna-belly smile, sitting on a folding chair with his bare feet on the hot top. He's a former Harlem gang leader, but now he's straight, a poet. He says we love LeBron -- where we means the basketball people who matter in New York. He also says something else. And this is where Maverick should cover his eyes.

"Look at Ray Allen, Paul Pierce, KG -- these guys sacrificed their careers for the championship. LeBron has to want it that bad. LeBron came in as a brand, getting $90 million from Nike. Shit. There's almost not much room to go after that. Kobe looks up at the rafters, he sees championship banners. That's inspiration. LeBron looks up and sees nothing. That's why the campaign for him to move to New York is so important. We have a history here," says Gotti. "We love LeBron here. But he needs to just do it, know what I mean?"

What he means is, enough of the talk. Like any talent, like any promise, it is only as good as its execution. We've got to sit and wait. Witness.

LeBron's great bed is quilted in the authenticity of Nike and Coca-Cola, in the swooshes and the snaking scripts of eminence, and that's all good, but he needs to work on the LeBron brand itself -- the emotion, the game, and the game face. He has to be the indisputable best, on the court and off.

LeBron's good friend Jay-Z part-owns the Nets, which are moving to his native Brooklyn in 2010, the same year LeBron will be free of his Cleveland contract. A move from Cleveland won't guarantee a championship, or five. But merely existing in the biggest media spotlight in the world will help the brand, will get LeBron nearer to owning the court of consumer veneration.

At an All-Star Weekend banquet that Jay-Z hosted with LeBron, one attendee recalls, "Jay-Z talked of a tomorrow when these two monuments to music and basketball will transform the rules of engagement for the iconic performer. He talked of making history."

Indeed, if these two perfect storms collide, it will be as meteoric as Hannah Montana French-kissing an American Girl doll at the Teen Choice Awards.

LeBron playing for the Nets "would be a dream for me," says Jay-Z. "But he's my friend first. I want the best for him wherever he is. He's my friend before he's a commodity."

It will help Jay-Z, just like Kobe winning helps sell sneakers, which helps LeBron. Brotherhood, lookin' out. Friendship and family, remixed with money and talent and fame and street cred, partnering the best of one world with the best of another.

"My logo," LeBron says, "is expanded now. An LB with a two-three and a crown underneath it." He points to it on his shoes. "You can see it right here, too." He moves the massive, winking bling he wears around his neck aside to expose the LeBron logo on his T-shirt. The necklace, a gift from Jay-Z, is a cluster of diamonds the size of a child's hand in the shape of Jay-Z's own logo, for his Roc-A-Fella Records.

Logo on top of logo, coiled snakes, sweethearts cheek to superstar cheek.

Now all he must do is win. And when he does, the logos will ignite -- an incandescent fire show scored with hip-hop and popping with exploding orange rubber -- and melt into each other. The two brands will beat as one. Bigger than Jordan, dunking higher than the sun. This is LeBron's silent vow, and Jay-Z's (and the world's) fervent expectation.

No comments:

Post a Comment